Mindfulness is a practice that has gained significant popularity in the world of performance. Though definitions for mindfulness vary, I like the one by Joshua Summers and Amy Baltzell: “Mindfulness refers to being aware of what’s happening in the present moment…It is the simple awareness of what is unfolding in real time, right now, just as it is.”

The benefits of recognizing what’s happening in real time seem obvious: if your mind is constantly being distracted, important information is likely to be missed. But how do mindfulness practices actually impact performance? The origin of the word provides insight into its philosophical underpinnings.

The term mindfulness is loosely translated from the Buddhist practice sati, which aims to to cultivate awareness of mind and body. However, sati itself translates to “memory” or “retention.” Thus, the practice of mindfulness is not just about awareness, but also remembering to come back to the present moment.

No matter the context of your performance environment, your attention is constantly being pulled in different directions. Even when you aren’t “performing” your mind still wanders away without your consent—it’s just what minds do. The reason mindfulness is becoming a more popular tool in performer’s arsenals is because it not only promotes a greater sense of awareness, but also serves as a tool for training training one’s attention. And as Peter Haberl famously noted: “Attention is the currency for performance.”

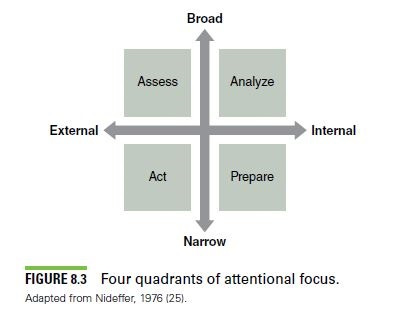

To understand the impact of mindfulness, let’s first look at the different styles of attention. Attention can be categorized based on it’s breadth (broad and narrow) and depth (internal and external). This creates four different attentional quadrants:

broad-internal

broad-external

narrow-internal

narrow-external

Each of these quadrants allow for different forms of attentional processing that can either help or hinder performance, depending on the task. The key is not only recognizing where your attention is placed within these quadrants, but being able to effectively shift between them in real time. Developing a mindfulness practice can enhance your ability to do both. In doing so, you give yourself the chance to recognize when your attention has shifted to the wrong quadrant and reorient it to support the task you’ve set out to execute.

Imagine a fire department’s battalion chief (BC) arriving on scene at a structural fire. Their job is to assess the situation, analyze an appropriate strategy, and direct the various battalions of firefighters on site how to execute. This would follow a attentional shift from broad external, to broad internal, to narrow external. Assess, analyze, act. This cycle is repeated over and over until the fire is extinguished.

But let’s look at how this might go wrong. Imagine a BC who gets stuck using a broad internal focus of attention, reviewing every possible strategy and outcome over and over again in their head, debating which is the best and weighing various options. Experts call this analysis paralysis, the inability to make a decision and execute due to over-analyzing a situation. The result for the BC in this case would be delayed action, or even inaction, which would ultimately leave the battalions and other civilians at risk.

People often think of mindfulness as focusing on a single thing for a very long time, but as we can see from this example, that’s only part of it. Mindfulness is about developing mental agility. A fire is an extremely dynamic and volatile environment, constantly changing with each minute. Mindfulness practice can train a BC to recognize if their attention is misplaced and seamlessly re-focus it to meet the demands of the changing conditions.

The mind will wander. It will get stuck. It will ruminate. In fact, research suggests that the mind wanders 50% of waking hours! Mindfulness allows you to practice recognizing when this happens and return to what matters here and now. Over time, the cycle of wander, recognize, return, and execute becomes faster and more efficient, enabling you to recover from mind wandering more quickly.

Ultimately, it’s that ability to come back (from mind wandering) to the task at hand that will strengthen your mindfulness the most when you are in a game or competition. — Summers & Baltzell, The Power of Mindfulness

5 Mindfulness Practices

Now that I’ve nerded out on the science, let’s look into some application. Here are five practices that can help you mindfully train your attention.

Noting. Knowing when your mind has wandered takes practice. It requires you to pay attention to your attention, which might seem strange at first. Noting practices can help you get more familiar with the nature of mind wandering by labeling what your mind is doing. When you notice your attention has drifted, try noting what it is doing with a descriptive label like “thinking”, “feeling”, or “hearing.” Then, bring it back to your focal point (e.g., breath, mantra, object, etc.) This demonstration from Headspace is a great guide. Don’t feel like you have to formally meditate to practice noting. You can do this practice while answering emails, studying, running, or working out.

Yoga Nidra. Yoga nidra is a very simple yoga practice similar to a body scan. A script/video prompts you while laying flat on your back with your eyes closed. If your mind wanders, note it and gently bring your attention back to your body (as directed by the script). This is also a great way to become more familiar with sensations resulting from the mind-body connection.

Dishwashing. Dishwashing can be a boring task that is prime for mind wandering. Practice mindfully washing your dishes by engaging your senses. Notice the colors, textures and movement that you can see. Feel the various temperatures and surfaces. Hear the clinking of the glass or streams of water hitting the pan. You may even notice the smell of the dish soap. If your mind drifts off, return your attention to these various sensations. Small practices like this are reps in training your attention.

Rubber band reminder. Place a rubber band or hair tie on your wrist before setting out for practice, work, or a long bout of studying. When you recognize your mind wandering, switch the rubber band from one hand to the other. This is meant to be a kinesthetic reminder to refocus your attention. You can even add a slow, deep breath to help reset yourself. If you find yourself switching all the time, that’s okay. Don’t be discouraged by the number of times you’ve switched from one hand to the other. The important thing is that you are recognizing when your attention has drifted.

Mindful breathing. Find a comfortable position, either seated upright or laying down on your back. Set a timer for 3-5 minutes (or longer if you feel comfortable). As you settle in, begin to notice the sensation of your breath and where it’s most noticeable in the body. Perhaps it’s in the upper part of the chest, or maybe lower down toward the belly. Approach each breath with an attitude of curiosity and interest, noticing the natural rhythm that your body uses and the length of the breaths that you take. Again, use the breath as an object of focus, coming back to the breath each time you notice your attention has drifted. You can try this on your own, or with an audio guide from Headspace, Calm, or free versions on YouTube.

Mindfulness takes many forms, meaning you can develop a practice that’s right for you. No matter what that looks like, the key is consistency. Just like any other skill, attention can be trained with deliberate and consistent practice. And just as you would with anything else you are trying to learn, start small and gradually work your way up. The more you exercise that mindfulness muscle, the stronger your attention becomes.